By Julius Alexander McGee

As the climate crisis escalates, the contradictions of the nation-state as both a facilitator and regulator of capital become increasingly apparent. The increase of natural disasters sparked by global warming have produced civil unrest and calls for change to our current social structures. These calls for change include a Green New Deal; divestment from fossil fuel industries; and a redistribution of wealth, all of which threaten the existing mechanism of capital accumulation. In response, the state has turned to the disaster capitalist playbook, turning the risk of civil unrest into new modalities of capital accumulation that maintain the status quo. This includes the creation of new low carbon markets that recapitulate pre-existing modalities of capital accumulation[1]. Recent attempts by nation-states to mitigate global warming through the creation of low carbon markets reveal how the climate crisis is being used to facilitate the expansion of capital into markets of data accumulation. This expansion is characterized by a process where data is created, collected, and circulated to generate wealth. Specifically, data extracted from low carbon technology to improve operational efficiencies ultimately functions to increase overall energy demand, as vast quantities of electricity are necessary to store data on computer servers. Such processes, unfortunately, of course, serve to undermine climate mitigation efforts. Further, the datafication of capital enhances surveillance technology that is used to disenfranchise Black and Brown communities through enhanced policing. Police departments around the United States as well as the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (also known as ICE) are using data to target communities that are left most vulnerable by the unrest of the climate crisis[2]. Meanwhile, lithium, an alkali metal essential to many low-carbon technologies is mined at the expense of indigenous communities in South America in response to increased demand for electric vehicles (henceforth EVs) and large-scale batteries required to store deployable renewable energy. Simply put, these outcomes reveal the racial character of economic development and the tendency for capital to maintain the settler colonial project that established capitalism as a system of social organization.

The automobile industry and widespread electrification were each established in the United States by dispossessing Black, Brown, and indigenous communities. The automobile industry thrived in the United States after the states demolished Black owned businesses and homes to build highways, and electrification was used to dispossess Black farmers of their wealth[3]. Moreover, the fossil fuels used to power automobiles and electricity are extracted on land dispossessed from indigenous people[4]. Indeed, it is increasingly clear that the continual dispossession and disenfranchisement of Black, Brown, and indigenous communities the world over is the true engine of capital accumulation. Specifically, by maintaining the historical expropriation of populations outside the terrain of capitalist production such that processes of uneven development favoring privileged Westerners might continue even in the face of socio-ecological instability. This paper intends to demonstrate how state policies aimed at creating low carbon markets are positioned as a reactionary force under disaster capitalism, which create new modalities of capital accumulation. I illustrate some of the key functions of this emergent phenomenon by examining the relationship between state sponsored low carbon markets and big data — a dynamic interplay that, despite appearances, fosters further dependence on fossil fuels through the dispossession of Black, Brown and indigenous communities around the world.

First, I explore the crisis that facilitated the datafication of capital -- the dot-com bubble burst of the early 2000s. Second, I explore the implications of the crisis that facilitated the creation of low carbon markets -- the crisis of the fossil economy. Third, I examine how low carbon markets perpetuate the datafication of capital such that data supplants fossil fuels as an organizing structure of the system of capitalism. I conclude by exploring how the internal dynamics of capitalism as a system are maintained through the combination of these two wings of the high technology sector.

The dot-com bubble burst and the rise of data as capital

In the neoliberal era, modalities of capital accumulation that emerge in the wake of social, economic, and ecological crises (be they actual or perceived), facilitate the redistribution of wealth from poor to rich through combined and uneven development[5]. Abstractly, this usually means new capital is created for the wealthy to own, new revenue streams are created to preserve the status of the middle class (that simultaneously undermine their stability), and new mechanisms of extraction are created that target/create the dispossessed -- this is what Naomi Klein refers to as “disaster capitalism”. In essence, disaster capitalism recapitulates the dynamics of capital accumulation in response to crises by passing down the risk from the wealthy to the poor.

In response to the dot-com bubble burst of 2000 as well as the events of September 11th, the Federal Reserve (the central banking system of the United States) continuously lowered interest rates for banks to help the United States’ economy emerge from a recession[6]. This created new capital in the form of AAA-rated mortgage-backed securities, because banks were incentivized to lend in order to generate new revenue from interest on loans[7]. Specifically, banks relied on individual home mortgages as a revenue stream by passing the Federal Reserve’s lower interest rates down to middle class homeowners who could take out cash from their homes through mortgage refinancing or cash-out refinancing to counteract stagnating wages. The federal reserve lowered interest to 1% in 2003, where it stayed for a year. In that time, inflation jumped from 1.9% to 3.3%. However, this proved to be extremely volatile due to lending practices that targeted Black and Brown communities in the United States with predatory loans. The subsequent Great Recession of 2008, disproportionately decimated wealth within Black and Brown communities through housing foreclosures, which redistributed wealth upwards, widening the racial wealth gap[8]. As Wang says, “these loans were not designed to offer a path to homeownership for Black and Brown borrowers; they were a way of converting risk into a source of revenue, with loans designed such that borrowers would ultimately be dispossessed of their homes”[9]. The transfer of capital from the productive sphere into the financial sector of the economy resulted in the financialization of capital via dispossession, breathing new life into the system through the construction of a new frontier for capital.

The dot-com bubble burst of the early 2000s was a crisis created by failed attempts to transform the technology of the internet into capital. Internet companies during this time absorbed surplus from other markets through investments but failed to turn a profit, creating a crisis that was solved through finance capital and the transfer of risk from wealthy to poor. In the 1990s and early 2000s, internet companies merged with media corporations to create a new frontier for capital based on the increasing popularity of the internet. For example, the America Online (AOL) Time Warner merger, seen as the largest failed merger in history[10], represented a merger of the largest internet subscription company and one of the largest media corporations in the United States. However, this merger failed after dial-up internet was supplanted by broadband -- a much faster and more efficient way to use the internet. Broadband connections, which allowed for continuous use of the internet, helped usher in the Web 2.0 era. Unlike its predecessor, Web 2.0 is defined by internet companies, such as Google, whose value derives in part from its ability to manage large databases that are continuously produced by internet users[11]. Investments in internet technology in the form of data, as opposed to software tools such as internet browsers (e.g., Netscape), transforms data into a modality of capital accumulation akin to fossil fuels. Data, like fossil fuels, supplants pre-existing modalities of capital accumulation by refining their ability to produce a surplus. Thus, whereas the dot-com bubble burst was produced because the internet could not turn a profit after absorbing the surplus of other markets, Web 2.0 is defined by its ability to enhance the surplus produced by other markets by refining their mechanisms of capital accumulation. In the proceeding section I explore how fossil fuels as capital are based on the continued oppression of Black, Brown, and indigenous communities in order to demonstrate how data is supplanting fossil fuels as capital.

Fossil fuels and the cycle of dispossession

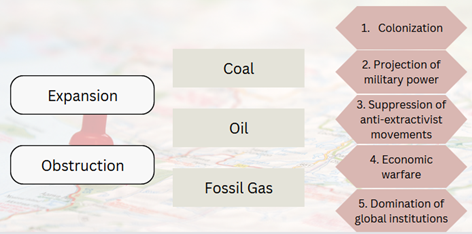

Fossil fuels have been an emergent feature of capital accumulation since they were first tied to human and land expropriation at the start of the industrial revolution in Great Britain. Factory owners in British towns used coal to power the steam engines that manufacture textiles from cotton, which was picked by enslaved Africans on land stolen from indigenous peoples. This tethered the consumption and production of coal to the expropriation of enslaved Africans and indigenous ecologies. As a result, coal, alongside enslaved Africans and indigenous ecosystems, became capital -- a resource that could be converted into surplus. Eventually, the steam engine gave the industrial bourgeoisie primacy over the plantation system that preceded it. Coal became the central driver of capital accumulation, which has borne an unsustainable system rife with contradictions. The natural economy, once based on human and land expropriation, gave way to the fossil economy, which uses fossil fuels to extract profit from human and ecological systems.

Prior to the “industrial revolution” the contradictions of human and land expropriation were apparent in the multitude of slave revolts across the West Indies; in San Domingo, Jamaica, Barbados, etc. These rebellions were not simply slave revolts, they were outgrowths of the contradictions of the plantation system, which were apparent from the time they were established. As Ozuna writes, “centuries of sustained subversive activity prompted colonial authorities to rethink their relationship to the enslaved, and oftentimes, make concessions to preserve the body politic of coloniality”[12]. That is, the fossil economy emerged as a way to avert the crisis of the plantation system.

The ability to manufacture cotton into textiles at an accelerating rate through the consistent use of coal, which was abundant on the island of Great Britain, became the precedent for colonial expansion in the United States, as well as the slave trade. Thus, human and land expropriation were fused to fossil fuel production and consumption. To put it succinctly, the fossil economy is an outgrowth of the plantation system, which automizes labor to efficiently accumulate capital. In supplanting the “natural economy” coal, and eventually petroleum, became emergent forms of capital accumulation that shifted the apparent contradictions of human and land expropriation.

The fossil economy has never transcended the contradictions embedded in human and land expropriation. The climate crisis consolidates the dialectical tension of fossil fuel production and the expropriation of humans, land, and human relationships with land. Likewise, the inability of nation-states to address the climate crisis is embedded in an unwillingness by ruling classes to address the core contradictions of capital accumulation. To address the climate crisis in a socially and ecologically sustainable way these contradictions must also be addressed. The climate crisis can be averted without addressing the contradictions of human and land expropriation, but such attempts will cost more in human life and ecological longevity by recapitulating human and land expropriation through the construction of new modalities of capital accumulation. In the same way that coal enabled the industrial bourgeoisie to expand capital accumulation while deepening its contradictions in centuries prior, data will recapitulate capitalism today.

Low carbon markets as disaster capitalism

Low carbon markets, such as cap-and-trade, carbon taxes, and consumer tax rebates are market-based, regulatory, environmental policies that seek to disincentivize environmental degradation by establishing a competitive market for low carbon technology to compete with fossil fuel-based markets. The logic of these policies is to encourage fossil fuel companies to pay for the future ecological cost of their markets and to use the funds obtained from these policies to establish new markets that can replace fossil fuels.

In the case of cap and trade (perhaps the most widely used strategy), a central authority allocates and sells permits to companies that emit CO2, which allows them to emit a predetermined amount of CO2 within a given period. Companies can buy and sell credits to emit CO2 on an open market, allowing companies that reduce emissions to profit from companies’ that do not. This approach was first established over thirty years ago in the United States to phase out lead in gasoline, and sulfur dioxide emissions from power plants that resulted in acid rain[13]. In 2003, the European Union adopted a cap-and-trade approach to CO2 emissions to reach emission reduction goals established during the Kyoto Protocol. Since then, more than 40 governments have adopted cap-and-trade policies aimed at reducing CO2 emissions while introducing minimal disruption to dominant economic processes[14].

If we accept the reality that fossil fuels were used to stave off the crisis of the plantation system and maintain capital accumulation via expropriation of human and ecological processes, then it points to the possibility that any new energy source created to maintain capitalism as a system will recapitulate the human and ecological expropriation that is foundational to the system. Thus, economic policies that facilitate the construction of low carbon markets, and that do not question the emergent character of fossil fuels under capitalism, invariably create new frontiers for capital accumulation. Opening such frontiers has been a primary role of the state under capitalism.

The abolition of enslavement by nation-states across the capitalist system aided in efforts to stave off the crisis of the plantation economy by alleviating the political and ecological tension the slave trade created. Nonetheless, many nation-states continued to expropriate formerly enslaved Africans by forcing them into labor conditions that were conducive to the overarching dynamics of capitalism[15]. Further, other forms of expropriation (e.g., the coolie trade) in newly established colonies within Southeast Asia were made possible by and undergirded the technology produced via the fossil economy. Thus, similar to how capitalism recapitulated its internal dynamics following abolition, it recapitulates its internal dynamics in its efforts to transition off of fossil fuels.

This plays into what Naomi Klein termed the politics of disaster capitalism[16]. Under the impetus of averting a climate catastrophe, climate mitigation policies allow industries to profit from the perceived disasters that will be caused by the climate crisis. While the climate crisis is no doubt a real threat to life on this planet, the new orchestrators of disaster capitalism have successfully commodified climate change in perception and solution. The perception is commodified through the implicit narrative that the market is the only solution to a crisis of its own making. Sustainable energy companies, like Tesla Motors, suggest that they have proved “doubters” wrong by producing electric vehicles that perform better than their gasoline counterparts, implying that the only obstacle in the way of addressing the vehicle market’s contribution to the climate crisis is the vehicles themselves. This feeds into the tautological logic used to commodify the solution, which assumes that the market simply needs to reduce CO2 emissions and, because electric vehicles are less CO2 intensive than their gasoline counterparts, they result in less CO2 emissions overall. Nonetheless, because the market operates under the logic of capital accumulation, companies that profit from the disaster playbook are incentivized to create more capital with their surplus, and companies create this surplus capital through datafication.

The datafication of capital

Data operating as capital has three fundamental components that allow it to operate as a distinct form of capital that is dialectically bound to broader systems of exchange. (1) As capital, data is valuable and value-creating; (2) data collection has a pervasive, powerful influence over how businesses and governments behave; (3) data systems are rife with relations of inequity, extraction, and exploitation[17]. Like other forms of capital, data’s value derives from its ability to create a market irrespective of its utility. The creation of data hinges on its potential to generate future profits, and not on its immediate usefulness. As such, the goal of this section is to establish how data is transformed into capital, not how it is used by any particular firm or institution.

The disaster politics of the climate crisis are similar in character to the tactics used by Wall Street financiers in the wake of financial crises. However, in addition to using crises as a launching pad for capitalist plunder, the orchestrators of the disaster politics of the climate crisis take advantage of the groundwork laid by finance capital. This is best exemplified in the ascendency of Elon Musk, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur who rose to prominence through an unregulated data-driven financial tool, and subsequently became one of the world’s richest people, in part through his companies’ ability to transform the shock of the climate crisis into an endless opportunity for data capital accumulation.

In 1999 Musk co-founded X.com, one of the first online payment systems. It later merged with Confinity Inc. to become PayPal, which is one of the largest online payment platforms in the world today. Similar to other tech companies from Silicon Valley, such as Uber, PayPal functions as a deregulated variant of a pre-existing market. Musk and others recognized the “inefficiency” of checks and money orders used to process online transactions. Online payment platforms bypassed regulations applied to banks when processing payments and led to these inefficiencies; PayPal created a new payment system that regulated itself based on data instead of bureaucracy.

In many respects PayPal is a digital bank whose main activity is in data instead of finance. PayPal claims that the data it collects is used to increase the security of its transaction, allowing money transfers to occur faster and with more convenience[18]. PayPal obtains its revenue through processing customer transactions and value-added services, such as capital loans. Online payment platforms such as PayPal are increasingly blurring the lines between retail and investment banking, again. For example, the loans that PayPal distributes to businesses are based on PayPal transactions, which are enhanced by PayPal’s data collection techniques. Thus, instead of accumulating wealth from financial instruments, PayPal accumulates wealth from the data it obtains from transactions, which it uses to finance more businesses and expand the number of consumer transactions it processes. This reality on its own has numerous implications for the climate crisis, as data centers, which store data at an exponential rate, rely on fossil fuel energy to operate[19] -- a fact that we will return to later.

Online payment platforms have also become the shadow benefactors of financial deregulations. For example, the repeal of Obama-era financial regulations in 2016 (installed in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis) that required financial institutions to disclose fees and protections against fraudulent charges benefited online payment platforms who were also subject to these regulations until 2016[20]. Here one can see the interest of data and finance aligning around market deregulation. As Sadowski writes, “Like finance, data is now governed as an engine of growth. If financial firms are free to shuttle capital from country to country, then similarly technology corporations must also be free to store and sell data wherever they want.” This is an expansion of the neoliberal project that began decades ago.

Data, like finance, is being used as a transnational modality of capital accumulation that transforms the role of the nation-state in relation to capital. Similar to how the state became a “lender of last resort, responsible for providing liquidity at short notice”[21] to encourage finance capital, the nation-state is facilitating the rise of data capital through tax-credits, rebates, and cap and trade. To be clear, at the end of the day the state is merely supporting long standing markets of capital accumulation, such as transportation and electricity, by aiding their efforts to create capital from data. Moreover, the state’s encouragement of data capital’s accumulation is increasingly occurring under the veneer of efforts to mitigate global warming.

Bitcoin’s legacy of expropriation and the climate crisis

After his departure from PayPal Elon Musk founded Tesla, an electric vehicle and clean energy company, in 2003. As a company, Tesla manufactures and sells electric cars, battery energy storage systems, solar panels, and solar roof tiles. However, Tesla’s profits derive from more than just the sale of its products. For example, in the first quarter of 2021 the bulk of Tesla’s profits came from the sales of emissions credits to other automakers, and sale of its bitcoin holdings[22]. This represents the new reality created through the disaster politics of the climate crisis, which merges financial speculation and data capital.

Carbon credits sold by Tesla to other auto manufacturers, who would otherwise incur fines, allow Tesla to profit from environmental degradation. This is the goal of policies such as cap and trade, as Tesla is profiting from the production and consumption of its low-carbon commodities, which in theory should facilitate the rise of low-carbon markets at the expense of fossil fuel-intensive companies. In addition to cap and trade policies, Tesla benefits from a number of tax credits and rebates that exist across the United States and European Union to encourage growth in low carbon energy markets[23]. Similar to the way cap and trade is meant to incentivize low-carbon technology, the logic of tax credits and rebates is to encourage both producers and consumers to adopt cleaner energy practices as an alternative to fossil fuels by reducing the cost of implementation, and increasing overall capital accumulated from low carbon technology. In theory, this should progress the consumption of less CO2 intensive commodities at the expense of CO2 intensive commodities. However, by using a portion of these profits to buy bitcoin, Tesla is expanding its holdings through the speculative value of Bitcoin, which derives from the ongoing exchange of Bitcoins and the vast stores of energy used to validate these transactions, produce and distribute the currency, and store its data.

Bitcoin is a popular cryptocurrency, the value of which is determined by a decentralized database known as a blockchain. This is distinct from the valuation of fiat currency, which is typically an outcome of inflation rates and the internal working of a central bank. The data that determines Bitcoin’s value encapsulates the supply and demand of Bitcoin on the market (the same as fiat currencies), competing cryptocurrencies, and the rewards issued to bitcoin miners for verifying transactions to the blockchain. Instead of storing its data in a central location, the data used to verify Bitcoin transactions is stored on multiple interconnected computers around the world. Each time a transaction using Bitcoin occurs, an equation is generated to be solved by a computer in order to confirm the validity of the transaction. The transaction is then stored permanently on data storage devices in 1MB chunks of transactional information. The completed block is then appended to previously existing ones, creating a chain of data that stores the history of all Bitcoin transactions. In effect the Bitcoin blockchain contains the entire history of all transactions that have ever occurred through Bitcoin, and this blockchain is repeated across every data storage device, or node, that composes the Bitcoin blockchain network. Thus, every time a block is completed and chained to the previous blocks, the solution is distributed to every node in the network where the block’s authenticity (the solution to the equation) is verified, and subsequently stored.

As blocks are added to the chain, which verify new transactions through the solution of a complex mathematical equation, new Bitcoin are produced. The equations are structured to identify a 64-digit hexadecimal number called a “hash.” The difficulty of the equations is determined by the confirmed block data in the Bitcoin network. The difficulty of the equation is adjusted every 2 weeks to keep the average time between each block at 10 minutes[24]. “Miners,” those who solve the equations and thereby verify the transactions that make up each block are rewarded for this work with Bitcoin, making it a lucrative market activity in and of itself. Thus, miners are in competition with one another to create new blocks; the more computing power the higher likelihood of successfully earning more coins. Because computers need electricity to function, and more computationally intensive tasks require more electricity, the process of creating new Bitcoin is very energy intensive. A study published in the journal Nature Climate Change in 2018[25] warned that due to its high electricity demands and increasing usage, Bitcoin mining could put the world over the two-degree Celsius tipping point, which would lead to an irreversible climate catastrophe.

The decentralized structure of blockchains grants Bitcoin users a level of anonymity that is not accessible through traditional currency. Further, as data-based currency is not regulated as traditional currencies are, Bitcoin transfers can be cheaper than a traditional bank’s transactions. As a result, many Bitcoin transactions are money transfers that benefit from anonymity and “cheapness.” Because Bitcoin’s value is determined in part by the number of transactions, companies, such as Tesla, that trade Bitcoin for profit derive surplus from how Bitcoin is used. This has numerous implications as to how datafication is deriving surplus from the disenfranchisement of Black and Brown communities.

The climate crisis has created an impetus for the data-based currency, Bitcoin. For example, migrants from the nation-states of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua are increasingly using Bitcoin for remittances[26]. Remittances are funds sent as gifts to friends and relatives across national borders. They comprise more than 20% of El Salvador and Honduras’ GDP, and nearly 15% of Nicaragua and Guatemala’s GDP, as of 2020[27]. Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua have been ravaged by a five-year long climate change-induced drought, which reduced crop yields from corn and beans -- food staples in the region[28]. The recent drought coupled with oppressive government regimes that were supported by the United States’ neoliberal policies are themselves indirect drivers of these currency transfers–– resulting in large-scale migration out of these regions and into relatively stable and wealthy nation-states, such as the United States (where they will be exploited either in ICE detention centers, prisons, jails, or other low-paid wage labor most frequently available to migrants).[29].

Bitcoin has become an increasingly popular form of currency to send remittances through because (like PayPal) it is cheaper, more efficient, and subject to less regulation than most banks[30]. In early 2021, El Salvador made headlines by announcing that Bitcoin would become a legal currency[31]. The logic behind this move is that Bitcoin will make it easier for people who do not have access to a bank to transfer money back to El Salvador. Here we see an explicit example of how the politics of disaster capitalism facilitate the construction of new frontiers that recapitulate the environmental harm (e.g. climate change through increased use of fossil fuels) and generate surplus from the climate crisis. Specifically, patterns of migration onset by climate change and U.S. policy create space for new financial tools, such as Bitcoin to fill. The carbon intensity of Bitcoin recapitulates the environmental harm that is partially responsible for mass migration.

Data, renewable energy, and the expropriation of Black and indigenous peoples

Tesla’s investment in Bitcoin demonstrates how low carbon markets recapitulate the internal dynamics of the fossil economy, deriving surplus from the legacy of human expropriation and exasperating the climate crisis. In addition to creating capital from data in the form of Bitcoin, electric vehicle companies like Tesla also create their own data. For decades, automobile producers and rideshare companies have been increasing the data they collect from drivers in an effort to profit from an emerging data market. Everything from speed, breaking habits, vehicle position, and music preferences are collected from individual vehicles and sold to various interests[32].

Electric vehicles like Teslas collect and store far more data than their predecessors, and the amount of data collected grows with every new product line. This is due to the ever more complicated hardware and software that comes stock on new vehicles. Specifically, new vehicles are equipped with internal cameras that are capable of capturing video of drivers who use autopilot[33], the reaction of drivers just before a crash, as well as infrared technology to identify a driver’s eye movements or head position[34]. New vehicles also connect directly to smartphones, allowing third parties to collect data on a driver’s travel and driving habits. Further, states are beginning to put forth laws that require automakers to include driver monitoring systems, increasing the pace at which data is extracted from vehicles. For example, driver monitoring systems will be a part of the requirements for Europe’s Euro NCAP automotive safety program as of 2023[35]. All of this increases the demand for data centers to store new data collected from vehicles as well as the propensity for data to operate as capital.

While a large portion of the data is sold to third parties such as insurance companies who can use data to determine rates, repair shops that can use data to assist mechanics, and automakers who use data to improve their products, vehicle data is also being used to expand the police state. Companies like Berla Corporation are working with police departments to extract data collected from vehicles, which can be used to surveil the population[36]. Through third parties, police departments are able to access data from smartphones that have been linked with vehicles, giving them access to anything from text messages to GPS location[37]. Considering the broader structure of the police state, this data can be used to expand the scope, scale, and authority of an institutionally racist organization, furthering the dispossession of Black and Brown communities.

New policies implemented by the state, such as the United States’ proposed 1 trillion dollar infrastructure plan[38], include incentives to increase the consumption of electric vehicles, accelerating the number of vehicles that can extract data from drivers. While the goal of these incentives is to increase adoption of electric vehicles to mitigate climate change, the vehicle market will also benefit from the new data collecting techniques embedded in electric vehicles, which will exponentiate the data stored in centers. Moreover, most electric vehicles are still far more expensive than gasoline vehicles, making them only accessible to the middle or upper classes. Thus, efforts to encourage consumption, such as tax rebates to consumers, results in combined and uneven development as middle-class consumers increase their long-term savings while poor people are left out. Moreover, in the past cap and trade has resulted in higher gasoline prices, which means those left out may also absorb the cost of these policies on the petroleum industry[39].

The apparent silver lining in all of this is the rise of renewable electricity, which could theoretically reduce the amount of fossil fuels used to capture and store data. Crypto currencies and the data collected from an evolving vehicle fleet could theoretically, then, grow without deepening the climate crisis as long as they rely on renewable sources of electricity. Nonetheless, when it comes to capital, there is nothing new under the sun. The climate crisis itself is an outgrowth of the continuous dispossession of the natural economy. Fossil fuels are merely an energy source that aids in this process. The ability to transcend ecological boundaries has facilitated the slow death of populations around the world since before the widespread use of fossil fuels. The first sugar plantations were erected in Madeira and the Canary Islands, to help the Genoese outcompete their Venetian rivals in the European sugar market at the expense of the indigenous life dependent on these islands. Capital’s maturation has been on an ongoing journey of death and destruction. While tracing this legacy is beyond the scope of this paper, suffice it to say that we are currently at a crossroads in the narrative of capital. The disaster politics of the climate crisis and data capital have created a new frontier in the lithium mines of Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. These mines exist on indigenous land, which belongs to the Atacama people.

Renewable electricity, such as that drawn from wind and solar power, as well as EVs require large lithium batteries to store the energy they use[40]. Lithium, a major component in all of these batteries, is currently being mined at the expense of indigenous people. The Lickanantay who live in the Atacama salt flat of northern Chile, consider the water and brine of this land as sacred[41]. As a result of lithium mining, the Atacama water table is losing an estimated 1,750-1,950 liters per second[42], depleting the sacred resource of Lickanantay people. Moreover, it has been argued that the increased demand for lithium mining has led to a recapitulation of the old neoliberal playbook - military coups. Specifically, the 2019 ousting of then president Evo Morales in Bolivia has been called a coup d'etat against indigenous people in Bolivia[43] in favor of lithium mining interests.

Conclusion

These recent developments bring us full circle as we can now see the outcome of the disaster capitalist playbook. The state responds to a crisis that it has aided and abetted by creating a new frontier - the low carbon market. The crisis is not global warming per se, rather, the civil unrest that the climate crisis creates. This unrest is addressed through the commodification of both the perception and solution to climate change - e.g. sustainable products such as EVs. The widespread consumption of low carbon technology results in combined and uneven development, allowing the middle class to reduce the long-term cost of travel and electricity at the expense of the underclass who absorb the cost of “environmentally sustainable” technology by becoming more surveilled and incurring the added costs borne by the fossil fuel industry due to its shrinking market share. The widespread consumption of low carbon technology facilitates and accelerates the datafication of capital, expanding the demand for energy within capitalist markets. As of now this demand has been met by fossil fuel interests who have become the benefactors of data capital's need for cheap energy. Nonetheless, as the renewable energy market expands, the need for lithium, located on indigenous land will encourage the further dispossession of indigenous ecologies. In the end, the natural resources needed to produce EVs and the data they gather are a new lease for capital; a new loan for endless dispossession; a refinancing of the climate crisis.

Notes

[1] Sadowski, Jathan. “When data is capital: Datafication, accumulation, and extraction.” Big Data & Society 6, no. 1 (2019):

[2] Rani Molla “Law enforcement is now buying cellphone location data from marketers” February 7, 2020.

[3] Eric. The folklore of the freeway: Race and revolt in the modernist city. U of Minnesota Press, 2014.

[4] Simpson, Michael. “Fossil urbanism: fossil fuel flows, settler colonial circulations, and the production of carbon cities.” Urban Geography (2020): 1-22.

[5] Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Verso Trade, 2018.

[6] Kimberly Amadeo “Fed Funds Rate History: Its Highs, Lows, and Charts” September 24 2021

[7] Celi, Chris, “Redefining Capitalism: The Changing Role of the Federal Reserve throughout the Financial Crisis (2006–2010)”. Inquiry Journal. No. 3 (2011)

[8] Rakesh Kochhar and Richard Fry “Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of Great Recession” December 12th, 2014

[9] Wang, Jackie. Carceral Capitalism. Vol. 21. MIT Press, 2018.

[10] Rita Gunther McGrath “15 years later, lessons from the failed AOL-Time Warner merger” January 10, 2015.

[11] Tim O’Reilly “What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software” No. 4578 2007.

[12] Ana Ozuna. “Rebellion and Anti-colonial Struggle in Hispaniola: From Indigenous Agitators to African Rebels.” Journal of Pan African Studies 11, no. 7 2018: 77-96.

[13] Richard Conniff “The Political History of Cap and Trade” Smithsonian Magazine August, 2009;

[14] Brad Plumer and Nadja Popovich “These Countries Have Prices on Carbon. Are They Working?” The New York Times April 2, 2019.

[15] Sherwood, Marika, and Christian Hogsbjerg. "After Abolition: Britain and the Slave Trade since 1807." African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter 11, no. 1 (2008).

[16] Klein, Naomi. The shock doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. Macmillan, 2007.

[17] Sadowski, Jathan. “When data is capital: Datafication, accumulation, and extraction.” Big Data & Society 6, no. 1 (2019):

[18] Adam Dillon. “How Paypal Turns Customer Data into Smoother Safer Commerce” Forbes May 6th 2019.

[19] Tom Bawden. “Global warming: Data centres to consume three times as much energy in next decade, experts warn” The Independent. January 23rd 216.

[20] Matthew Zeitlin “Venmo Could Be A Big Winner As Obama-Era Financial Rules Are Scrapped” Buzzfeed February 28th 2017.

[21] Foster, John Bellamy. "The financialization of capitalism." Monthly review 58, no. 11 (2007): 1-12.

[22] Jay Ramey “Tesla Made More Money Selling Credits and Bitcoin Than Cars” Auto Week April 27th 2021

[23] https://www.tesla.com/support/incentives accessed 8/9/2021

[24] https://www.blockchain.com/charts/difficulty accessed 8/11/2021

[25] Mora, Camilo, Randi L. Rollins, Katie Taladay, Michael B. Kantar, Mason K. Chock, Mio Shimada, and Erik C. Franklin. “Bitcoin emissions alone could push global warming above 2 C.” Nature Climate Change 8, no. 11 (2018): 931-933.

[26] Enrique Dans. “Bitcoin And Latin American Economies: Danger Or Opportunity?” Forbes July 14, 2021

[27] World Bank Developmentl Indicators https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=SV accessed 8/13/2021

[28] Jeff Masters “Fifth Straight Year of Central American Drought Helping Drive Migration” Scientific American December 23, 2019

[29] Michael D McDonald. “Climate Change Has Central Americans Fleeing to the U.S.” Bloomberg Businessweek June 8, 2021

[30] Roya Wolverson. “Bitcoin is wooing the millions of workers who send their earnings abroad” Quartz Africa March 26, 2021

[31] Mitchell Clark “Bitcoin will soon be an official currency in El Salvador” The Verge June 9, 2021

[32] Matt Bubbers. “What kind of data is my new car collecting about me? Nearly everything it can, apparently” The Globe and Mail January 15, 2020

[33] Fred Lambert. “Tesla has opened the floodgates of Autopilot data gathering”. Electrek June 14, 2017

[34] Keith Barry. “Tesla's In-Car Cameras Raise Privacy Concerns” Consumer Reports March 2021.

[35] Euro NCAP. “In Pursuit of Vision Zero” https://cdn.euroncap.com/media/30700/euroncap-roadmap-2025-v4.pdf accessed 08/3/2021

[36] Mitchell Clark. “Your car may be recording more data than you know” The Verge December 28, 2020.

[37] Sam Biddle. “Your Car is Spying on you, and a CBP Contract shows the Risks” The Intercept, May 3, 2021.

[38] Niraj Chokshi. “Biden’s Push for Electric Cars: $174 Billion, 10 Years and a Bit of Luck” The New York Times March 31, 2021.

[39] Mac Taylor. “Letter to Honorable Tom Lackey” https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2016/3438/LAO-letter-Tom-Lackey-040716.pdf accessed 8/22/2021

[40] Xu, Chengjian, Qiang Dai, Linda Gaines, Mingming Hu, Arnold Tukker, and Bernhard Steubing. “Future material demand for automotive lithium-based batteries.” Communications Materials 1, no. 1 (2020): 1-10.

[41] Amrouche, S. Ould, Djamila Rekioua, Toufik Rekioua, and Seddik Bacha. "Overview of energy storage in renewable energy systems." International journal of hydrogen energy 41, no. 45 2016.

[42] By Ben Heubl. “Lithium firms depleting vital water supplies in Chile, analysis suggests” Engineering and Technology August 21, 2019.

[43] Kinga Harasim. “Bolivia’s lithium coup” Latin America Bureau October 7, 2021.