By Miriam Bak McKenna

Republished from Legal Form: A Forum for Marxist Analysis of Law

If the politics of gender have been dragged front and centre into public discourse of late, this shift seems to have evaded international legal scholarship, or legal scholarship for that matter. Outside feminist literature, discussions of gender continue to be as welcome as a fart in a phonebox among broader academic circles. Unfortunately, Marxist and historical materialist scholarship fare little better. Despite periods in the 1960s and early 70s when their shared belief in the transformative potential of emancipatory politics flourished, Heidi Hartman had by 1979 assumed the mantle of academic marriage counselor, declaring that attempts to combine Marxist and feminist analysis had produced an “unhappy marriage”. [1] Women’s interests had been sidelined, she argued, so that “either we need a healthier marriage, or we need a divorce”. [2] Feminists pursued the latter option and the so-called “cultural turn”–a move coinciding with the move away from the “modernist” agenda of early second-wave feminism towards postmodern perspectives.

Not all feminists, however, took the cultural turn or wholeheartedly embraced postmodernism. Many continued to work within broadly materialist frameworks. Silvia Federici, known prominently for her advocacy of the 1970s Wages for Housework demand, continued the Marxist feminist momentum in her advocacy and scholarship by overseeing a revision or perhaps even reinvention of materialist feminism, especially in the United States. Federici’s work on social reproduction and gender and primitive accumulation, alongside a small but active group of materialist feminists (particularly Wally Seccombe, Maria Mies and Paddy Quick), brought a new energy to materialist feminism, making the capitalist exploitation of labour and the function of the wage in the creation of divisions within the working class (starting with the relation between women and men) a central question for anti-capitalist debate. Drawing on anti-colonial struggles and analyses to make visible the gendered and racialized dimensions of a global division of labour, Federici has sought to reveal the hierarchies and divisions engendered by a system that depends upon the devaluation of human activity and the exploitation of labour in its unpaid and low-paid dimensions in order to impose its rule.

In this post, I argue that Federici’s work offers a rich resource for redressing the conspicuous absence of a gendered perspective within academic scholarship on materialist approaches to international law. Materialist analyses of systematic inequalities within the international legal field are as relevant now as they ever were, yet the sidelining of gender and feminism within both traditional and new materialism has long been cause for concern. A gendered materialism in international law, which casts light on the logic of capitalist socialization and which affords the social reproductive sphere equal analytical status, allows us to access a clearer picture of the links between global and local exploitation at the intersections of gender, race, and nationality, and provides new conceptual tools to understand the emergence and function of international legal mechanisms as strategies of dominance, expansion, and accumulation.

A Brief Portrait of a Troubled Union

In 1903 the leading German SPD activist Clara Zetkin wrote: “[Marx’s] materialist concept of history has not supplied us with any ready-made formulas concerning the women’s question, yet it has done something much more important: It has given us the correct, unerring method to explore and comprehend that question.” [3] In many respects this statement still rings true. While Marxism supplied means for arguing that women’s subordination had a history, rather than being a permanent, natural, or inevitable feature of human relations, it was quickly criticized for marginalizing many feminist (and other intersectional) concerns. Feminist scholars in particular called attention to the failure of some forms of Marxism to address the non-economic causes of female subordination by reducing all social, political, cultural, and economic antagonisms to class, and the tendency among many traditional Marxist scholars to omit any significant discussions of race, gender, or sexuality from their work.

Marxist feminists (as well as critical race scholars and postcolonial theorists) have attempted to correct these omissions with varying degrees of success. The wave of radical feminist scholarship in the 1960s produced a number of theories of women’s domestic, sexual, reproductive, and cultural exploitation and subordination. Patriarchy (the “manifestation and institutionalization of male dominance over women and children in the family and the extension of male dominance over women in society in general” [4]) emerged as a key concept that unified broader dynamics of female subordination, while gender emerged as a technique of social control in the service of capitalist accumulation. Within this logic some proposed a “dual-system theory” wherein capitalism and patriarchy were distinct systems that coincided in the pre-industrial era to create the system of class and gender exploitation that characterizes the contemporary world. [5] Others developed a “single-system theory” in which patriarchy and capitalism “are not autonomous, nor even interconnected systems, but the same system”. [6]

During the 1970s, discussions turned in particular to the issue of women’s unpaid work within the home. The ensuing “domestic labour debate” sought to make women’s work in the home visible in Marxist terms, not as a private sphere opposed to or outside of capitalism but rather as a very specific link in the chain of production and accumulation. By exploring its strategic importance and its implications for the capitalist economy on a global scale, this analysis helped show that other forms of unpaid work, particularly by third world peasants and homeworkers, are an integral part of the international economy, central to the processes of capital accumulation. However, the Wages for Housework Campaign was criticized for failing to engage with broader social causes and effects of patriarchal oppression, as well as for essentializing and homogenizing the women it discussed. [7] These criticisms contributed to deep divisions between feminist thinkers on the left. A majority were to follow the lead of those like Hartman, arguing that Marx’s failure explicitly to examine domestic labour, coupled with the “sex-blind” analysis of most Marxist theorists, had prevented Marxism from adequately addressing women’s working conditions. Describing this period, Sue Ferguson noted that the “festering (and ultimately unresolved) issue” fueling socialist feminist thought was the place of Marxist analysis. [8] This shift, meanwhile, was overtaken by the cultural turn in social theory and the question of “how women are produced as a category” as the key to explaining their social subordination, in which materialist issues such as the debate over domestic labour were largely discarded. [9]

WWF: Wages, Witches, and Fanon

Among the Marxist feminist scholars who stayed the course during the broader scholarly shift towards structuralism, a small group of materialist feminists, including Silvia Federici, began to expand the debates over the relationship between patriarchy and capital by integrating the complexities of various forms of reproductive labour into their work. Led by such notable figures as Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, Leopoldina Fortunati, Maria Mies, Ariel Salleh, and Federici herself, their work on the sphere of social reproduction, which had largely been neglected in Marxist accounts, brought new energy to the materialist debate. In particular, responding to the above-mentioned critiques, they shifted their perspectives to develop situated accounts of the role of women in the global geopolitical economy that incorporated overlapping issues of imperialism, race, gender, class, and nationality.

The arc of Federici’s scholarship mirrors to a large extent the broader shifts within late-twentieth century Marxist feminism. Inspired to pursue a PhD in the United States after witnessing the limitations placed upon her mother, a 1950s housewife, her arrival coincided with an upswing of feminist activity in U.S. universities. Federici’s first publication, titled Wages Against Houseworkand released in 1975, situated itself within the domestic labour debate, drawing on Dalla Costa and James’ arguments that various forms of coerced labour (particularly non-capitalist forms) and generalized violence, particularly the sexual division of labour and unpaid work, play a central function in the process of capitalist accumulation. This structural dependence upon the unwaged labour of women, noted Maria Mies, meant that social reproduction is “structurally necessary super-exploitation”–exploitation to which all women are subjected, but which affects women of colour and women from the global South in particularly violent ways. [10]

In Wages Against Housework, Federici expanded these social reproduction insights into a theory of “value transfer”, focusing on the dependence of capital on invisible, devalued, and naturalized labour. Contrary to the prevailing ideology of capitalism, she argues, which largely depicts labour as waged, freely undertaken, and discrete, the reality is that–especially where women are concerned–labour is often coerced, constant, proliferating, and uncompensated. “We know that the working day for capital does not necessarily produce a paycheck and does not begin and end at the factory gates”, she explains together with Nicole Cox in “Counterplanning from the Kitchen”. [11] Capitalism infiltrates and becomes dependent upon the very realm that it constructs as separate: the private life of the individual outside of waged work.

Central to Federici’s thesis is the need to analyze capitalism from the perspective of both commodity production and social reproduction in order to expand beyond traditional spaces of labour exploitation and consider all of the spaces in which the conditions of labour are secured. As Federici argues in Caliban and the Witch, traditional Marxist categories are inadequate for understanding fully processes of primitive accumulation. [12] She notes that “the Marxian identification of capitalism with the advent of wage labor and the ‘free’ laborer…hide[s] and naturalize[s] the sphere of reproduction”, and further observes that “in order to understand the history of women’s transition from feudalism to capitalism, we must analyze the changes that capitalism has introduced in the process of social reproduction and, especially, the reproduction of labor power”. [13] Thus, “the reorganization of housework, family life, child-raising, sexuality, male-female relations, and the relation between production and reproduction” are not separate from the capitalist mode of organization, but rather central to it. [14] The conflation and blurring of the lines between the spaces of production of value (points of production) and the spaces for reproduction of labour power, between “social factory” and “private sphere”, work and non-work, which supports and maintains the means of production is illustrated through her analysis of the household. Housework, Federici declares (and I am sure many would agree here) is “the most pervasive manipulation, and the subtlest violence that capitalism has ever perpetrated against any section of the working class”. [15] Housework here is not merely domestic labour but its biological dimension (motherhood, sex, love), which is naturalized through domestic violence, rape, sexual assault, and most insidiously through “blackmail whereby our need to give and receive attention is turned against as a work duty”. [16] For Federici, the situation of “enslaved women … most explicitly reveals the truth of the logic of capitalist accumulation”. [17] “Capital”, she writes,

Has made and makes money off our cooking, smiling, fucking”. [18]

In Federici’s historical analysis of primitive accumulation and the logic of capitalist expansion, both race and gender assume a prominent position. For Federici, both social reproductive feminism and Marxist anticolonialism allow historical materialism to escape the traditional neglect of unwaged labour in the reproduction of the class relation and the structure of the commodity. As Ashley Bohrer has explored, Federici, like many other Italian Marxist feminists, has drawn explicitly on the work of post-colonial scholars, most prominently Frantz Fanon [19], in developing their theories of gendered oppression. [20] In the introduction to Revolution at Point Zero, Federici explains how she and others drew on Fanon’s heterodox economics in expanding their analyses beyond the scope of the traditional capitalist spaces:

It was through but also against the categories articulated by these [civil rights, student, and operaist/workerist] movements that our analysis of the “women’s question” turned into an analysis of housework as the crucial factor in the definition of the exploitation of women in capitalism … As best expressed in the works of Samir Amin, Andre Gunder Frank and Frantz Fanon, the anticolonial movement taught us to expand the Marxian analysis of unwaged labour beyond the confines of the factory and, therefore, to see the home and housework as the foundations of the factory system, rather than its “other”. From it we also learned to seek the protagonists of class struggle not only among the male industrial proletariat but, most importantly, among the enslaved, the colonized, the world of wageless workers marginalized by the annals of the communist tradition to whom we could now add the figure of the proletarian housewife, reconceptualized as the subject of the (re)production of the workforce. [21]

Just as Fanon recasts the colonial subject as the buttress for material expansion among European states, so Federici and others argue that women’s labour in the home creates the surplus value by which capitalism maintains its power. [22] Federici contends that this dependence, along with the accentuation of differences and hierarchies within the working classes for ensuring that reproduction of working populations continues without disruption, has been a mainstay of the development and expansion of capitalism over the last few centuries, as well as in state social policy. Colonization and patriarchy emerge in this optic as twin tools of (western, white, male) capital accumulation.

Expanding upon Fanon’s insights about the emergence of capitalism as a much more temporally and geographically extended process, Federici regards the transition as a centuries-long process encompassing not only the entirety of Europe but the New World as well, and entailing not only enclosures, land privatization, and the witch hunts, but also colonialism, the second serfdom, and slavery. In Caliban and the Witch, she presents a compelling case for the gendered nature of early primitive accumulation, by excavating the history of capital’s centuries-long attack on women and the body both within Europe and in its colonial margins. For Federici, the transition was “not simply an accumulation and concentration of exploitable workers and capital. It was also an accumulation of differences and divisions within the working class, whereby hierarchies built upon gender, as well as ‘race’ and age, became constitutive of class rule and the formation of the modern proletariat”. [23] According to Federici, the production of the female subject is the result of a historical shift of economic imperative (which was subsequently enforced by those who benefited from such economic arrangements), which set its focus on women, whose bodies were responsible for the reproduction of the working population. [24] The goal was to require a “transformation of the body into a work-machine, and the subjugation of women to the reproduction of the work-force” [25], and the means “was the destruction of the power of women which, in Europe as in America, was achieved through the extermination of the ‘witches’”. [26] The witch–commonly midwives or wise women, traditionally the depository of women’s reproductive knowledge and control [27]–were targeted precisely due to their reproductive control and other methods of resistance. The continued subjectification of women and the mechanization of their bodies, then, can be understood as an ongoing process of primitive accumulation, as it continues to adapt to changing economic and social imperatives.

While a rich and engaging tradition of feminist approaches to international law has emerged over the past few decades, it has shown a marked tendency to sideline the long and multifaceted tradition of feminist historical-materialist thought. Similarly, within both traditional and new materialist approaches to international law, there has been a conspicuous sidelining of gender and feminism, along with issues of race and ethnicity. The argument for historical materialism in the context of international legal studies is not, as some critics have claimed, that women’s oppression ought to be reduced to class. Rather, the argument is that women’s experiences only make sense in the explanatory context of the dynamics of particular modes of production. However, this requires an adequate theory of social relations, particularly of social production, reproduction, and oppression, in order to sustain a materialist analysis that “make[s] visible the various, overlapping forms of subjugation of women’s lives”. [28]

It is my contention that Federici’s social-reproductive and intersectional theory of capitalism provides a path toward a more nuanced and sustained critique of the logic and structure of capitalism within the international legal field. This approach foregrounds the social–that is, social structures, relations, and practices. But it does not reduce all social structures, relations, and practices to capitalism. Nor does it depict the social order as a seamless, monolithic entity. Moving beyond traditional class-reductionist variants of historical materialism, capitalism emerges here as one part of a complex and multifaceted system of domination in which patriarchy, racism, and imperialism are fundamental, constitutive elements, which interact in unpredictable and contradictory ways.

As Federici’s scholarship has stressed, the importance of foregrounding social reproduction as part of the dynamic of capitalist accumulation, as facilitated by states and international institutions, is essential to any materialist analysis, including one of the international legal field. This is necessary for exploring women’s specific forms of oppression under capitalism, particularly as they are facilitated by the family and the state. For example, Federici’s insights into the domain of unpaid social reproduction and care work are useful for understanding women’s subordinated incorporation into labour markets, especially in the global South and in states affected by structural adjustment. Indeed, while the state largely facilitates women’s entry into the workforce, their categorization as “secondary” workers–“naturally” suited to care work and the fulfillment of physical and emotional needs, and “naturally” dependent upon men–has continually been reproduced to the detriment of their labour situation. [29]

While Federici’s social reproduction theory begins with women’s work in the home, she demonstrates that capitalism’s structural dependence upon unwaged and reproductive labour extends to regimes of domination predicated upon social control on the global plane (from slavery through the exploitation of immigrant workers to the genocide of indigenous peoples). In her account of primitive accumulation, power relations sustained through the construction of categories of gender, race, sex, and sexuality facilitate the creation of subjects predicated upon capitalism’s systemic needs. While the heterosexual family unit is one of the more visible ways in which this domination is socially reproduced, the relationship, Federici argues, is reproduced in many settings. The transformations of the neoliberal era–particularly the global reorganization of work fueled by the drive to impose the commodity form in ways that seek to harness and exploit labour in its unpaid and low-paid dimensions–are characteristic of this dynamic. Federici has also emphasized the fact that domestic workers and service providers have consistently been devalued as workers. [30] In doing so, she highlights one of the rhetorical gaps in the contemporary feminist movement: when women enter the waged work-force, they often enter into an exploitative relationship with other women (and men) with less social power. It is the latter’s labour, bodies, and time that provide the means for access to better conditions within the labour market.

This relation of exploitation is also prevalent in neocolonial forms of exploitation–called “the new enclosures” by Federici–which ensure that the affluent North benefits from social and economic conditions prevailing in the global South (for example, through transnational corporations’ access to cheap land, mineral, and labour resources). Capitalism, Federici argues, depends not only on unwaged housework, but on a global strategy of underdevelopment in the global South, one that relies upon the stratification of and constructed division between otherwise common interests. “Wagelessness and underdevelopment”, she argues, “are essential elements of capitalist planning nationally and internationally. They are powerful means to make … us believe that our interests are different and contradictory.” [31]

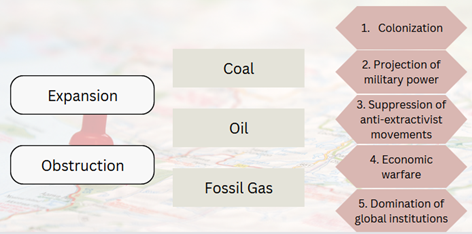

Federici’s depiction of patriarchy, the state, and capitalism as interacting forces, together with her focus on relational, overlapping regimes of domination and their attendant systems of control, points the way toward a new way of understanding intertwined techniques and discourses of power in the international legal field. Capitalism’s reliance upon multiple types of exploitation, multiple forms of dispossession, and multiple kinds of subjects is visible in broader themes of international law. It is, for instance, visible in the overlapping dynamics of control that mark the history of colonial expansion, as well as the emergence in the nineteenth century of sovereign hierarchies and various legal mechanisms that ensure patterns of dominance, expansion, and accumulation in the international sphere.

An examination of the historical and contemporary role of international law in perpetuating these dynamics of oppression prompts us to address the specific processes whereby these categories are produced and reproduced in international law. Examples include norms surrounding marriage and the family, the production of the category of the temporary worker, and the illegal immigrant whose disenfranchisement is the necessary condition of their exploitation. Much the same can be said for trade, property, taxation policy, welfare and social security provision, inheritance rights, maternity benefits, and support for childcare (or the lack thereof). In the context of the gendered dynamics of globalization, we can examine the manner in which the devaluation of female labour has been facilitated by international institutions, notably the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, and through development initiatives such as micro-finance and poverty reduction strategies. Federici has also revealed the complicity of ostensibly neutral (and neutralizing) discourses such as development, especially when pursued with the stated objective of “female empowerment”, in glossing over the systemic nature of poverty and gendered oppression. These dynamics are ultimately predicated upon law’s power to create, sustain, and reproduce certain categories.

Usefully, Federici’s relational theory of subjectivity-formation also allows us to move beyond gender and race as fixed, stable categories, encouraging a new understanding that helps us detect more surreptitious gendered tropes and imaginaries in the structure of international legal practice and argumentation. One example is the set of narratives that surround humanitarian intervention. Indeed, as Konstantina Tzouvala has suggested, one of the glaring deficiencies in the socialist feminism proposed by B. S. Chimni is the absence of an explanation of how gender, race, class, and international law form an inter-related argumentative practice. [32]

Conclusion

Writing some ten years after David Schweickart lamented that analytical Marxism “remains a discourse of the brotherhood” [33], Iris Marion Young noted that,

[O]ur nascent historical research coupled with our feminist intuition tells us that the labor of women occupies a central place in any system of production, that the gender division is a basic axis of social structuration in all hitherto existing social formations, and that gender hierarchy serves as a pivotal element in most systems of social domination. If traditional Marxism has no theoretical place for such hypothesis, it is not merely an inadequate theory of women’s oppression, but also an inadequate theory of social relations, relations of production, and domination. [34]

Young’s defense of a “thoroughly feminist historical materialism” [35] is as relevant today as ever. While great in-roads have been made within materialist approaches to various disciplines, including international law, the continued tendency to marginalize issues of gender (along with issues of race and sexuality) greatly undermines the soundness of such critiques. In pointing to issues of social reproduction, racism, sexual control, servitude, imperialism, and control over women’s bodies and reproductive power in her account of primitive accumulation, Silvia Federici highlights issues that must occupy a prominent place in any materialist treatment of international law.

Miriam Bak McKenna is Postdoctoral Fellow and Lecturer in International Law at Lund University.

Notes

Heidi Hartman, “The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism” [1979], in Lynn Sargent (ed.) Women and Revolution: The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism–A Debate on Class and Patriarchy (London: Pluto, 1981) 1.

Ibid., 2.

Clara Zetkin, “What the Women Owe to Karl Marx” [1903], trans. Kai Shoenhals, in Frank Meklenburg and Manfred Stassen (eds) German Essays on Socialism in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Continuum, 1990) 237, at 237.

Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 239.

Pat Armstrong and Hugh Armstrong, “Class Is a Feminist Issue”, in Althea Prince, Susan Silvia-Wayne, and Christian Vernon (eds), Feminisms and Womanisms: A Women’s Studies Reader (Toronto: Women’s Press, 1986) 317. See, for example, Hartman, “Unhappy Marriage”; and also Sylvia Walby, Gender Segregation at Work (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1988).

See, for example, Lise Vogel, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1983); Iris Marion Young, “Beyond the Unhappy Marriage: A Critique of Dual Systems Theory”, in Lydia Sargent (ed.), Women and Revolution: A Discussion of the Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism (Boston: South End Press, 1981) 43.

See Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race, and Class (New York: Random House, 1981).

Sue Ferguson, “Building on the Strengths of the Socialist Feminist Tradition”, 25 (1999) Critical Sociology 1, at 2.

See, for example, Rosalind Coward and John Ellis, Language and Materialism (London: Routledge, 1977) and Juliet Mitchell, Psychoanalysis and Feminism (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1975).

Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour, 1st edition (London: Zed Books, 1986).

Nicole Cox and Silvia Federici, Counterplanning from the Kitchen: Wages for Housework–A Perspective on Capital and the Left (Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1975), 4.

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (New York: Autonomedia, 2004), 8.

Ibid., 8–9.

Ibid., 9.

Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland: PM Press, 2012), 16.

Silvia Federici, Wages Against Housework (Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1975), 20.

Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 89.

Federici, Wages Against Housework, 19.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove, 2004 [1961]).

Ashley Bohrer, “Fanon and Feminism”, 17 (2015) Interventions 378.

Federici, Revolution at Point Zero, 6–7 (original emphasis).

Ibid., 7.

Federici, Caliban and the Witch, 64 (original emphasis).

Ibid., 145.

Ibid., 63.

Ibid.

Ibid., 183.

28. Chandra Talpade Mohanthy, Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 28.

29. Daniela Tepe-Belfrage, Jill Steans, et al., “The New Materialism: Re-Claiming a Debate from a Feminist Perspective”, 40 (2016) Capital & Class 305, at 324.

30. Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (Oakland: PM Press, 2012), 65–115.

31. Ibid., 36.

32. Konstantina Tzouvala, “Reading Chimni’s International Law and World Order: The Question of Feminism”, EJIL: Talk! (28 December 2017).

33. David Schweickart, “Book Review of John Roemer, Analytical Marxism“, 97 (1987) Ethics 869, at 870

34. Iris Marion Young, “Socialist Feminism and the Limits of the Dual Systems Theory”, in Rosemary Hennessy and Chrys Ingraham (eds), Materialist Feminism: A Reader in Class, Difference and Women’s Lives (New York: Routledge, 1997) 95, at 102.

35. Ibid (original emphasis).